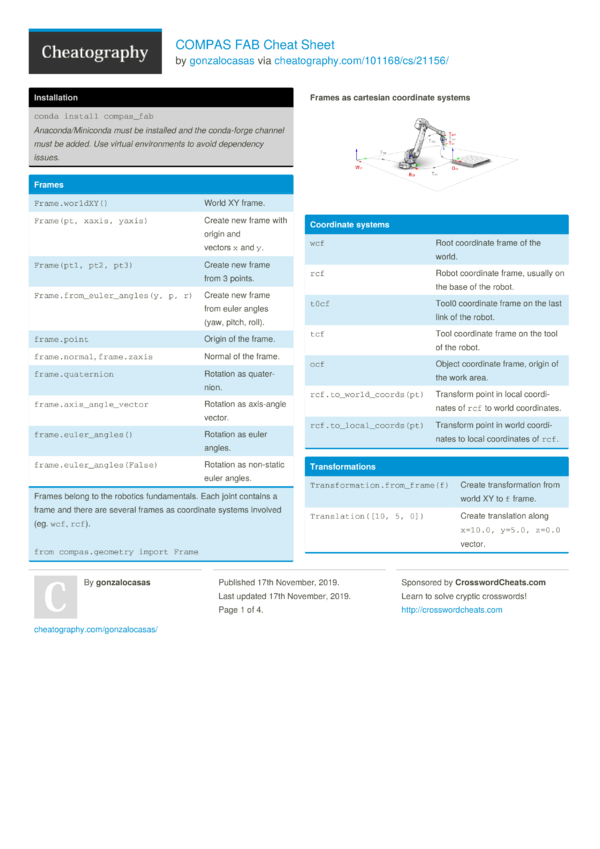

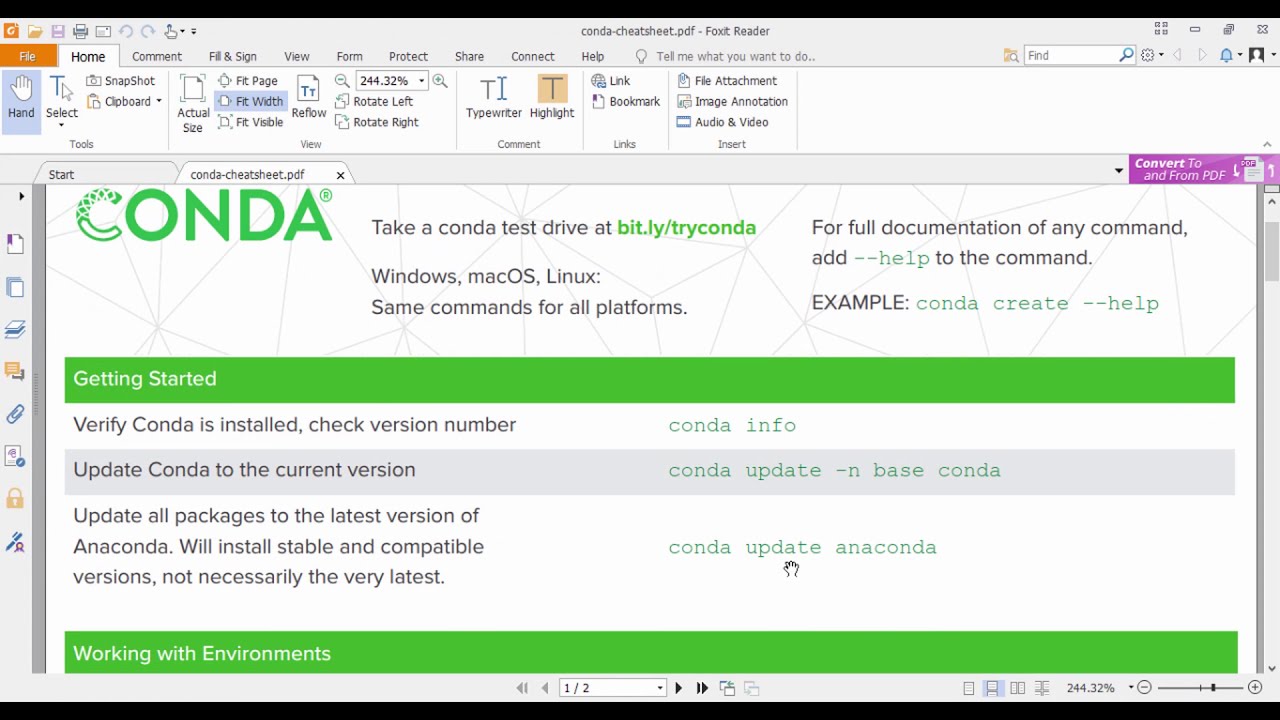

View AnacondaCheatSheet from ACG 785016 at Miami Dade College, Miami. ANACONDA CHEAT SHEET See full user documentation for Anaconda docs.continuum.io/anaconda BEFORE YOU. See the conda cheat sheet PDF (1 MB) for a single-page summary of the most important information about using conda.

Managing Conda and Anaconda

|

|

|

Managing Environments

| Active environment shown with |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Managing Python

| |

| Install different version of Python in new environment |

Managing .condarc Configuration

| |

| |

| Add a new value to channels so conda looks for packages in this location |

Managing Packages, Including Python

| View list of packages and versions installed in active environment |

| Search for a package to see if it is available to conda install |

| Install a new package NOTE: If you do not include the name of the environment, it will install in the current active environment. |

| |

| Search for a package in a specific location (the pandas channel on Anaconda.org) |

| Install a package from a specific channel |

| Search for a package to see if it is available from the Anaconda repository |

| Install commercial Continuum packages |

| Build a Conda package from a Python Package Index (PyPi) Package |

Removing Packages or Environments

|

|

|

|

Notes

- Based on the cheat sheet from Conda Docs

- Converted by Charles

Deploying conda environments inside a container looks like a straight-forward conda install. But with a bit more love for details, you can optimise the process so that the build is faster and the resulting container much smaller.

This post intends to be an addition to a Jim Crist-Harif’s “Smaller Docker images with Conda” and a condensed version of the long-read I’ve published at the same time as this post. If you want to understand the reasoning of the tips here, you should head over to the long-read. Otherwise, I hope that this post serves as a cheatsheet to lookup every time you want to put a conda environment inside a (Docker) container.

The dependencies of your to-be-containerised environment should be specified as you typically specify a conda environment using an environment.yml file. An example looks like:

While this is a nice human-readable file, it doesn’t provide you with reproducibility across runs. Thus we pin the requirements down to the actual build of each package using conda-lock. This has the advantage that with the given lockfile, you can recreate the exact environment every time. Also, the lockfiles switch conda into a special mode where it only installs packages but doesn’t do a new solving step. This dramatically improves installation time.

Conda Remove Cheatsheet

To generate a lock file from an environment.yml you can use the following command:

And install it using:

As the base of your images, you should pick one the following three containers that come with a basic / minimal conda installation. In the case of using one of the conda-forge provided images, we always pick the ones that come with mamba included as this speeds up the installation dramatically.

continuumio/miniconda3: Debian Buster with a minimal conda installation configured for the Anacondadefaultschannel (continuumio/miniconda3:4.9.2is 437MB in uncompressed size)conda-forge/mambaforge3: Ubuntu 20.04 with a minimal conda and mamba installation configured withconda-forgeas the default package source (conda-forge/mambaforge:4.9.2-5is 411MB in uncompressed size)conda-forge/mambaforge-pypy3: Ubuntu 20.04 with a minimal conda and mamba installation configured withconda-forgeas the default package source and using PyPy instead of CPython (conda-forge/mambaforge-pypy3:4.9.2-5is 449MB in uncompressed size)

If you do not plan to use your container interactively but only want to package a service inside of it, you should use multi-stage builds. In the first stage, you should take one of the above containers and build the conda environment in it. As the second stage, you should pick the most minimal container that is required to run the conda environment namely gcr.io/distroless/base-debian10. This container only contains the bare essential like a libc but no shell or package manager at all.

A Dockerfile for this multi-stage approach looks like the following:

This picks up the ideas of Jim’s post. While conda environments come with all batteries included, batteries weigh quite a bit and you don’t need all of them at runtime. Thus you should get rid of those that you know that you will not need.

- Delete the conda metadata in

conda-meta - Delete C/C++ includes in

include(only required at compile-time) - Delete

libpython*.so.*; this only works in the case where your entrypoint is calling thepythonexecutable which is statically linked, i.e. contains the same symbols aslibpython.so. This wouldn’t work if we had an application that would embed the Python interpreter itself. - Delete

__pycache__withfind -name '__pycache__' -type d -exec rm -rf '{}' '+' - Delete

pipwithrm -rf /env/lib/python3.9/site-packages/pipas we don’t plan to install any packages - Delete

lib/python3.9/i{dlelib, ensurepip}from the standard library - Delete

lib{a,t,l,u}san.soas the various sanitizers are not used during production - Delete the binaries like

x86_64-conda-linux-gnu-ld, sqlite3, opensslfrombin. In most cases, these binaries are not used for running a service - Delete

share/terminfoas we don’t expect to run a terminal

Conda Check Env

The above tips boil down to the following statement. Be aware though that not every file listed here can be safely removed in all cases.

Conda Env Create

Title picture: Photo by Jonas Smith on Unsplash